Canada’s Blue Camas Meadows: A Story of Plant+Human Co-Evolution

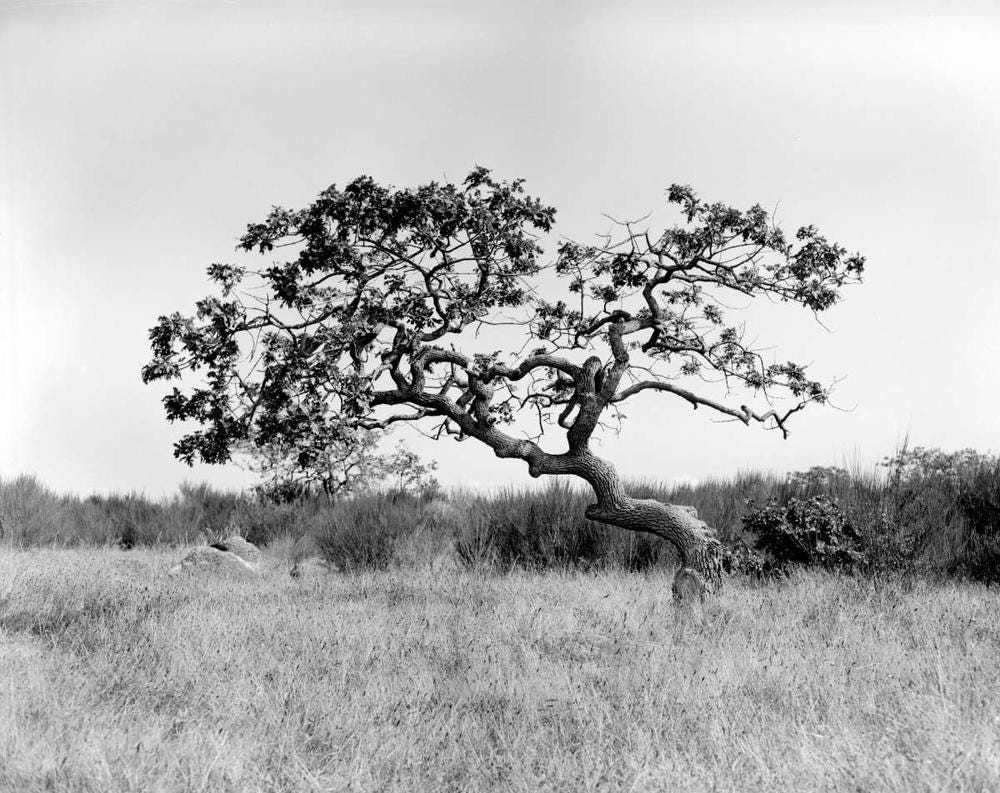

Garry Oak Ecosystem aka White Oak, Oregon Oak or Oregon White Oak

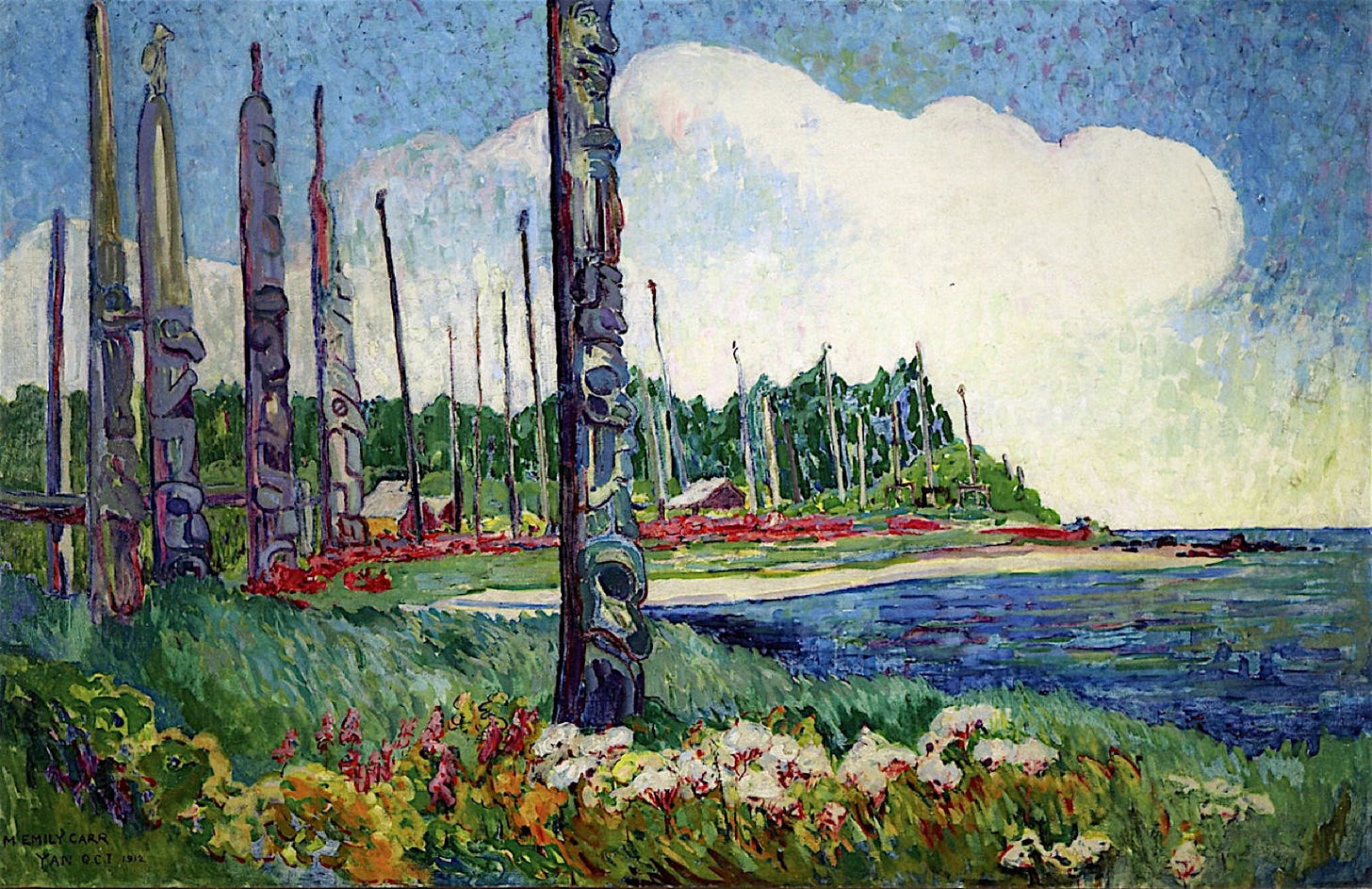

There's nothing quite like British Columbia’s coastal Garry oak ecosystem in the spring; a softly undulating dreamscape of purply-blue Camassia punctuated by low twisted oaks and mossy boulders. It’s beauty can be overwhelming.

But this landscape doesn’t exist in a vacuum, it carries a complex story of humans and plants evolving together. The tale of a unique symbiotic ecosystem, once highly prized and now fighting extinction. It is a case study in hard won survival, stewardship and biodiversity through human involvement, in a time when nature is often seen as something disconnected from humans.

Today, we’ll work our way through the botanical, scientific and cultural significance of the Garry oak system. It’s evolution and care through indigenous stewardship including it’s colonial journey. Plus, we’ll see where things stand today as a view towards restoration, reconciliation and protection rises to the surface.

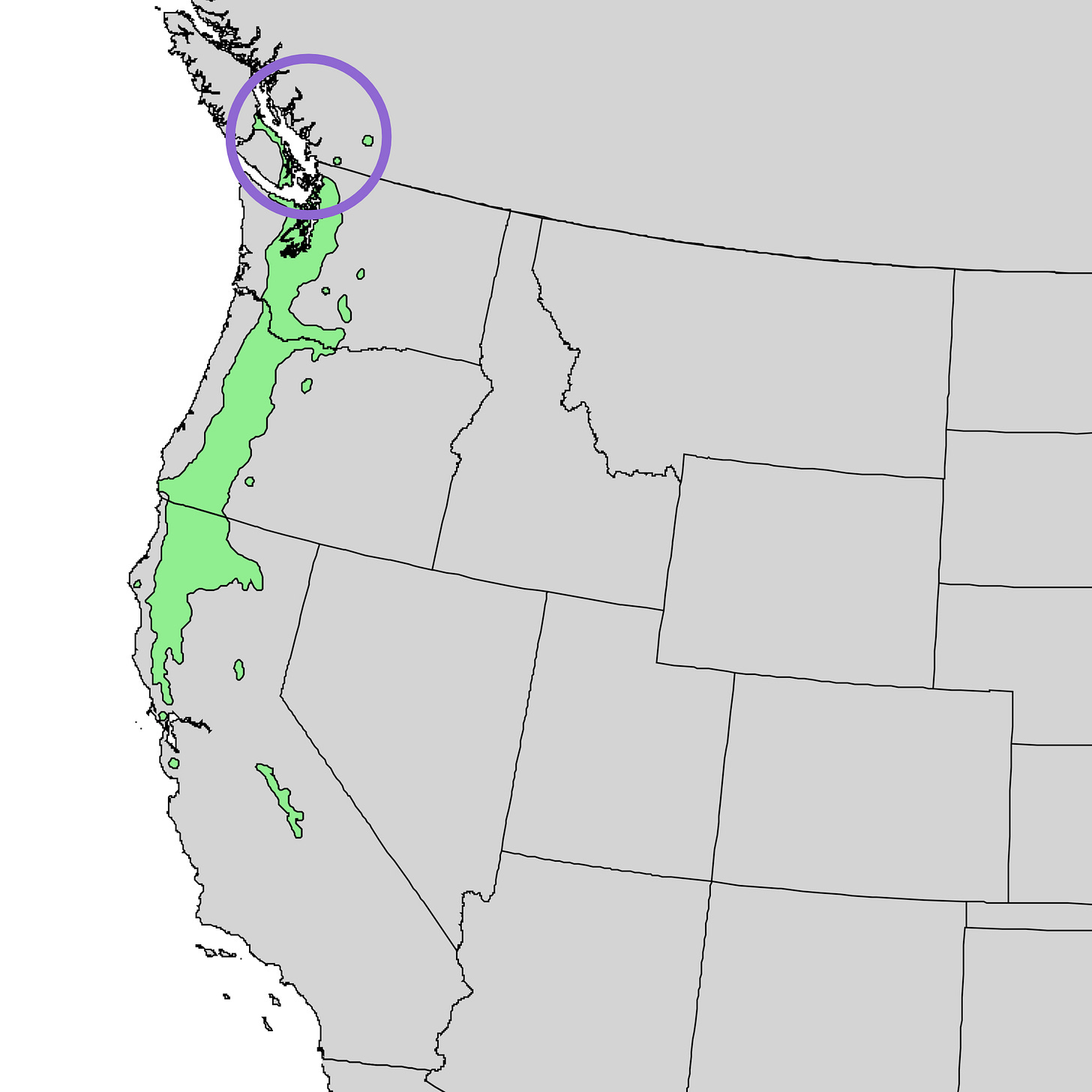

Natural Range

With a huge natural range, Garry habitat once included large swaths of the coastal Islands and mainland, south along the Pacific coast all the way to Northern California (USA). Today, it’s meadows are relegated to smaller more isolated pockets. Including those that we’ll chat about today: southwestern Vancouver Island, the southern Gulf Islands (in the Straight of Georgia) and a few other rare patches on the mainland.

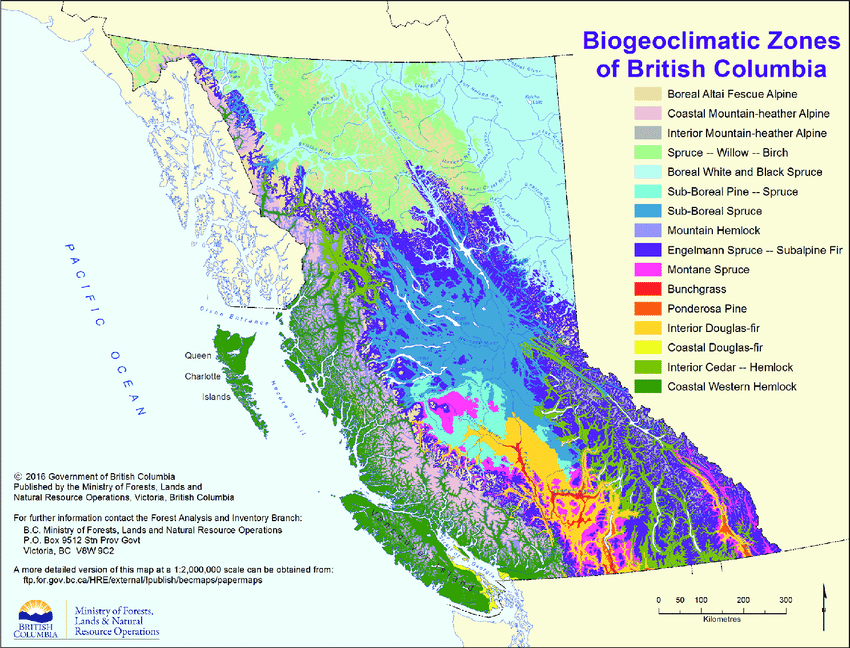

Coastal Climate

Here on the west coast of British Columbia, the climate is considered sub-mediterranean. Seeing somewhat warm, low pressure weather systems in close proximity to the mild ocean currents of the Salish Sea. Hence, snow and hard frosts are rare in winter months and much of the vegetation remains green year round. Summers tend to be cool and drier than those of the temperate rainforest typically found in other parts of BC. In fact, the high hours of sunshine routinely cause browning and periods of dormancy for many plants throughout the summer months.

Diverse Habitat

Besides its beauty, Garry oak systems also contain one of the highest rates of plant diversity within the province of British Columbia (an area 4X the size of Great Britain). Supporting, more than 700 plant species, 100+ species of birds, 7 amphibians, 7 reptiles and 33 mammal species (with 800+ insect and mite species directly associated with Garry oak trees alone).

Notably, the ecosystem features a great number of specialized flora that occur no where else in Canada, with more than 70 rare and endangered species currently identified. So while Garry oaks and camas (Camassia quamash and Camassia leichtlinii) are considered key, they are certainly not the only species worth noting.

There are in fact several distinct types of sites associated with Garry oak, each supporting slightly different plant communities.

Plant Communities

The deepest soils contain the richest and most drought-tolerant plant communities. Here, mature Garry oaks (Quercus garryana) with extensive canopies sit over a dense layer of shrubbery including:

Rosa nutkana (Nootka Rose)

Symphoricarpos albus (Common Snowberry)

Holodiscus discolor (Ocean Spray)

Ribes sanguineum Pursh var. sanguineum (Red-flowering Currant)

Oemleria cerasiformis (Indian-plum)

This leaves little space for the more herbaceous layer, although some forbs may occur in sparse groupings.

Median depth soils tend to occur on gentle drier slopes. Where the oaks form a more open canopy with less shrub material. Instead, a better developed herbaceous layer fills the space. Both types of Camassia can be found in abundance along with grasses and forbs including:

Melica subulata (Alaska oniongrass)

Elymus glaucus (Blue wildrye)

Carex inops (Long-stoloned sedge)

Sanicula crassicaulis (Pacific sanicle)

Dichanthelium acuminatum (Western Witchgrass)

Achnatherum lemmonii (Lemmon's needlegrass)

Allium acuminatum (Hooker's onion)

Allium cernuum (Nodding onion)

Delphinium menziesii (Menzies' Larkspur)

Eriophyllum lanatum (Woolly Sunflower)

Erythronium oregonum (White Fawn Lily)

Fritillaria affinis (Chocolate Lily)

Olsynium douglasii (Satinflower)

Plectritis congesta (Sea Blush)

The shallowest and driest soils are usually found on slopes over and around bedrock outcrops. Shrubs rarely survive here, more typical vegetation includes:

Lonicera hispidula (Pink Honeysuckle)

Festuca idahoensis (Idaho fescue)

Elymus glaucus (Blue Wildrye)

Bromus carinatus (California brome)

Sanicula crassicaulis (Pacific Sanicle)

Rock crevices sometimes hold deeper soil pockets that can support dwarfed trees but the very shallowest areas are generally populated by ground covers, moss and lichen including:

Dicranum scoparium (Broom Moss)

Racomitrium canescens (Rock Moss)

Polytrichum juniperinum (Juniper Haircap Moss)

Selaginella wallacei (Wallace's Selaginella)

Sedum spathulifolium (Spoon-leaved Stonecrop)

Claytonia perfoliata (Miner's Lettuce)

Montia parviflora (Small-leaved Montia)

Cerastium arvense (Field Chickweed)

Lotus micranthus (Small-flowered Bird's-foot Trefoil)

Indigenous Agroecosystems: 3000+ years

It should be noted that what we currently understand about indigenous cultivation and use of camas is pieced together through many sources. There is little direct evidence that has remained intact after countless losses of what was once a vast cultural heritage. What we can be certain of, is that the Garry oak ecosystem is anthropogenic, it requires human intervention in order to thrive. And on the South Island (where the majority of habitat remains), that comes from countless generations of the Lək̓ʷəŋən (Songhees) Nation.

Warning, there may be outdated references to indigenous peoples in some image captions and quotes. I’ve kept the original information as is, for historical transparency.

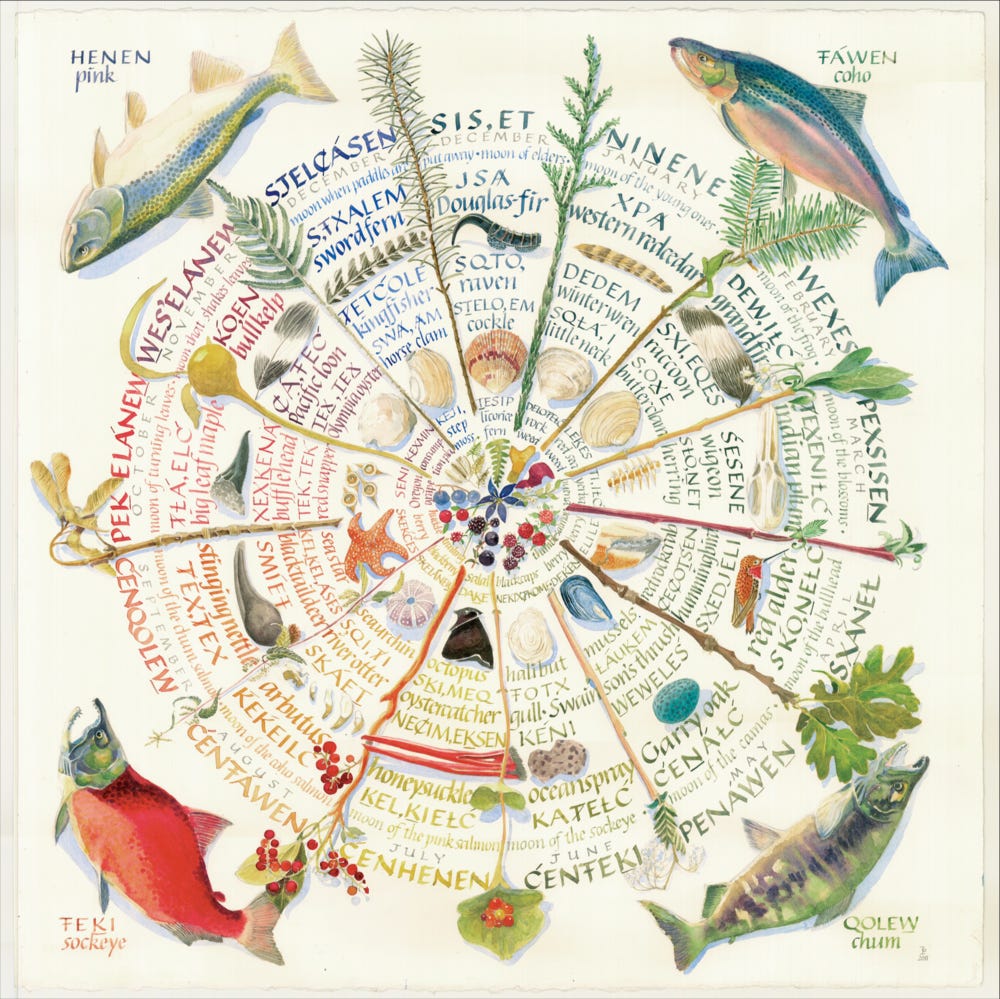

The larger group of Coast Salish cultures represent a highly sophisticated society deeply connected to the sea and forest in which they are seated. Here there are several keystone species that sustain it: Pacific salmon (Oncorhynchus sp.), Western red cedar (Thuja plicata) and Blue camas (Camassia sp.). These resources plus many adjacent ones were part of a large network of sustainable agroecosystems. These are management systems that fit somewhere in-between natural landscapes and agricultural ones. Their reciprocal methods follow natural processes rather than attempting to control them. Resources are stewarded and encouraged in the places where they thrive with low-scale intervention. The population then moves between the sites seasonally to perform the necessary maintenance and harvesting in a symbiotic relationship. This included Garry oak meadows, hunting grounds, fisheries and clam gardens just to name a few. The reliable influx of resources, along with those that could be gathered or foraged, provided the diverse materials needed to build a flourishing society.

Camassia as a Keystone Crop

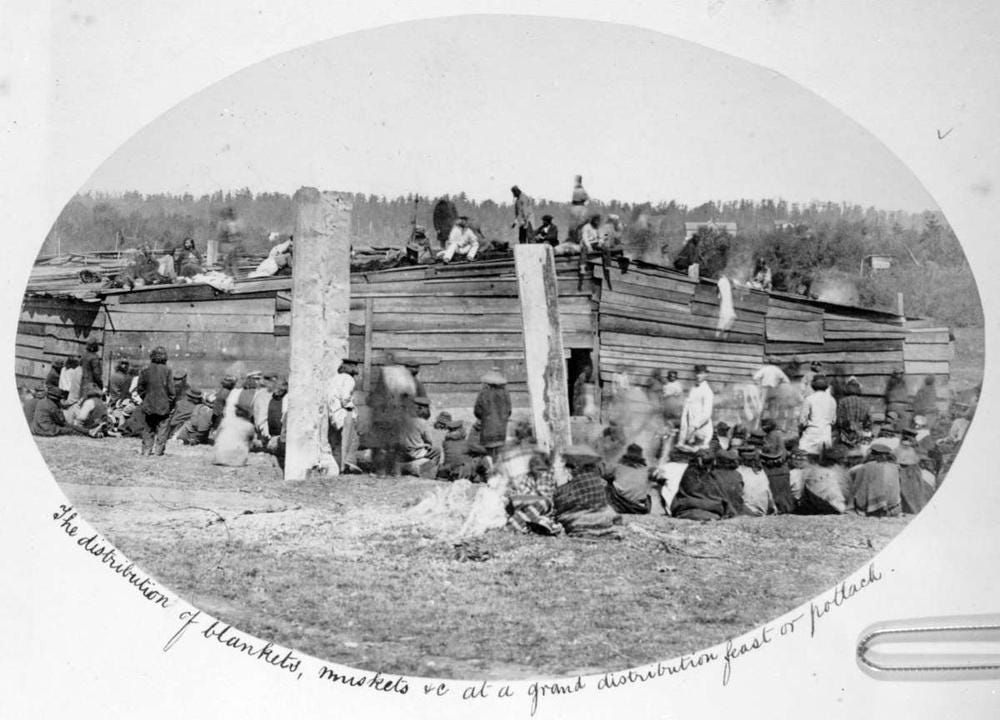

The camas found in the Garry oak ecosystem was a significant food source and by extension of great cultural importance. It provided a sweet, starchy staple, full of fibre and nutrients that could be preserved and consumed in a number of ways. As a result, the plant provided year-round sustenance, allowing for long-distance travel, trade opportunities and sophisticated cultural traditions. It became a key to large-scale community gatherings (potlatch etc.) where social interaction, government and religious activities, and an exchange of knowledge took place.

Plots

Camas meadows were highly valued spaces. Some were maintained in close proximity to dwellings for immediate use while others were further away, including outlying islands. The fields themselves were divided into plots, each tended by an individual family. These were marked by stakes, lines of cobbles or existing landmarks (rocks, outcrops etc). Highly productive plots were defended by their owners and passed down to family members, while less advantageous areas may have been open to communal use. Salish women took the lead in the majority of the tasks that involved camas, from cultivation through to cooking and storage. Europeans observed that the ownership seemed to cover the camas themselves rather than the land. In a similar way to the ownership of fishing rights, ancestral names and medicinal knowledge.

Cultivation and Harvesting

Much of the cultivation of Cammassia took place in the warmer months of the year, between March and September.

Low-intensity controlled burns may have been used as the camas was emerging in early spring. Any grass, ferns or other new growth was burnt off, opening space for the desired plants to grow and making the harvest easier. The two main species bloom in spring, Camassia quamash (Common Camas) April-June and Camassia leichtlinii (Great Camas) May-June.

The most intensive cultivation took place while harvesting; just as the blooms faded and while the bulbs were holding the maximum amount of nutrients and flavour. Specialized hardwood sticks (with fire hardened tips) were used to dig pockets of bulbs up, working across a plot little by little. "Digging in small sections, using the stick to turn and uproot the bulbs, harvesting the best tasting mid-sized ones while replanting the rest, including seeds, as they went along". One observer noted, "it is surprising to see the aptitude with whch the root is dug out. A botanist, who has attempted the same feat with his spade, will appreciate their skill". Weeding was likely done at the same time, removing any unwanted plants (especially white-flowering, Toxicoscordion venenosum aka Death camas) and rocks as they worked the soil.

There is a saying that is often repeated with Camassia, "the more you dig the better it grows".

Harvest may have taken days to weeks depending on the location and size of the meadows, as well as the amount of labour available. Several families often travelled together to areas further afield, working to bring in sizeable stockpiles. Over a single season, one family could collect as many as 10,000 bulbs.

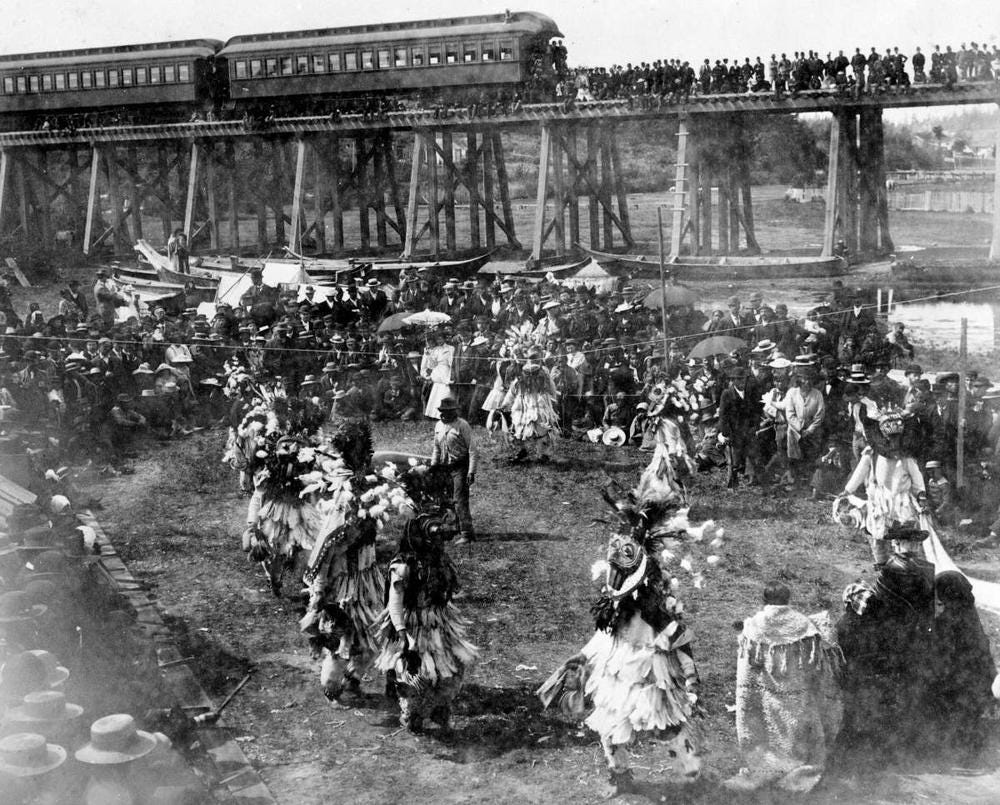

Ritual and ceremony likely accompanied the work, possibly before and after harvest, along with traditional songs sung during the task. Settlers observed, "digging is a great season of 'reunion' for the women of the various tribes, and answers with them to our hay-making or harvest homecoming." As one can easily imagine, the seasonal encampments with multiple generations gathered in one space, facilitated the sharing of knowledge and cultural traditions. The largest meetups also included horse racing, gambling and dancing in addition to trading, feasts and more.

Post-harvest, low intensity flash burns were lit. Moving fast across fields in mid-summer, they kept shrub material at bay and aided nutrient cycling. The nature of the controlled burns removed encroaching conifers and shrubs but left mature hardwood trees like the Oak intact. This maintained the openness of fields and encouraged deer and elk to feed there. The animals would graze on any remaining seedlings, opening the area even further while making themselves easy prey to hunters.

The burns made good use of nitrogen-fixers like Bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum) and Clover (Trifolium sp.) releasing the nutrition they held into meadow soils. Additionally in some areas seaweed may have been laid over the freshly dug and levelled beds before burning to further increase fertility and encourage new growth.

Cooking and Storage

The high moisture content of camas bulbs makes them difficult to store in a raw state. And as their main carbohydrate (inulin) requires heat in order to be converted into a more digestible sugar, the bulbs were usually steamed shortly after harvest. Said to smell like vanilla cake and taste of brown sugar, the dark sticky bulbs were often consumed directly out of the pit ovens used to roast them. Additionally they could be flattened into small bricks and dried after cooking for later use. It's believed that they were packed in bentwood boxes (which had multiple uses including cooking) or baskets made of cedar (a natural insect repellant) ready for winter use, trade, travel and/or feasts and ceremonies.

Dried camas could be boiled or soaked in water for use as needed or ground into a type of flour and mixed with water to form dough. Prolonged boiling would yield a coffee-like, sweet hot beverage, or molasses type syrup used to sweeten and flavour other dishes. In fact, it was the only source of sweetness available in the area at the time, further adding to its value.

Cooking took place in pits that could be constructed almost anywhere for the lengthy process (up to 36hrs) of steaming. Specific methods likely varied from group to group and depending on site conditions available resources etc.. One observer noted, "You dig a hole about two feet deep and about four feet across. In this you lay fine dry wood, then heavy sticks parallel across it, then rocks across the heavy sticks. Now light the fire. When the rocks get red hot this means get ready. When the rocks drop down, take the ashes out and level off the ground with a good hard stick. Then lay on kelp blades (Nereocystis luetkeana), which are easy to gather in quantity, salal (Gaultheria shallon) branches, sword ferns (Polystichum munitum) and the camas. ..You must fix it so that no dirt gets in and yet leave it all full of holes (air spaces). Leave a hole at the top and when it is covered pour in more than a bucket of fresh water. When the water seeps through to the rocks, it steams up. Put grass on top, then about four inches of dirt, then build a fire on top of that. Leave it all night until the next afternoon."

Camas weren't always cooked on their own, clams, other root vegetables and meats could be added to cook at the same time. With various materials included for flavour (bark, seaweed, lichen etc) and colouring (red alder bark, also used in tattoo pigment, made camas pink). At times several families would contribute to an active pit and then divide the food when done. The camas were eaten as part of a varied diet, with 2-3 bulbs considered an adequate serving in addition to other dishes (click here, for some modern info and recipes for anyone wanting to try their own camas dishes).

Excess bulbs were taken to trade with groups in areas that couldn't produce enough of their own supplies. This included the BC mainland as well as other coastal sites and islands accessible by canoe. In fact camas (outside of the Garry oak system) could be found as far east as Alberta and south into California.

Colonization: late 1700s-early 1900s

Spanish explorers first entered the coastal waters of BC in the late 1700s, and Captain Cook landed on what became known as Vancouver Island in 1778. But, the real colonization of the area came with the Hudsons Bay Company (HBC) in the mid-1800s.

When settlers first sighted the landscape they were taken by the vast open meadows that greeted them. These beautiful and fertile spots seemed perfect for their needs. A lack of fences, crop rows and other signs of traditional European use lead them to the conclusion that they were totally natural sites, "dropped from the clouds", as though they had just been waiting for them. As the first wave of HBC employees moved in, the landscape was quickly, dramatically and irrevocably changed. In the end, at least four major company compounds were built in close proximity to camas meadows.

The HBC's main trading station on the island, Fort Victoria, was established in 1843. It joined an already extensive network that followed the mainland river systems, connecting interior fur trading centres with the coast of British Columbia and by extension Europe.

Indigenous peoples were an essential part of the settlers initial survival and success. They were willing to provide much needed labour and trade important food stuffs like salmon and camas. "It has been recorded that early explorers and settlers made resourceful products with camas bulbs, although many of these preparations were already Indigenous innovations... Prolonged boiling, for example, resulted in the conversion of the camas bulbs into a molasses, which could have been used as a sweetener for coffee or for making pies. Father Anthony Ravalli recalled that he, "made two gallons of splendid alcohol from about three bushels of camas by fermenting". Despite all their inventiveness, however, the settlers quickly recognized the digestive side effects of camas over- consumption. Father Nicolas Point explained" ...the digestion is accompanied by very disagreeable effects for those who do not like strong odors or the sound that accompanies them". David Douglas also commented on the flatulence caused by eating too much camas, saying that the "strength of wind" almost blew him out of a Indigenous (Chinook) dwelling."

Goldrush & Cashing In on ‘Natural Resources’

As the colony expanded, the radius of cultivated land grew to include many fields packed with European crops including oats, peas and wheat. Field potatoes, likely brought over from Fort Langley, began to replace camas in many ways. As the Salish began to lose access to the land, their food sovereignty and security slipped away with it. By the mid-1800s, the HBC were granted title to the entire island on the condition that it be colonized. The city was officially named, Victoria, and a townsite laid out.

The frantic energy of the gold rush hit hard as fortune seekers travelled from all over the world to the promising discoveries of the Cariboo and Yukon. Victoria, a small settlement of 230 souls, was suddenly inundated. "the Commodore - ...entered Victoria harbour on Sunday morning, April 25, 1858, just as the townspeople were returning homeward from church. With astonishment, they watched as 450 men disembarked - typical gold-seekers, complete with blankets, miner's pans and spades and firearms; and it is estimated that within a few weeks, over 20,000 had landed". The price of city plots went from $25 one week to $3000 the next. The rapid expansion further strained resources and with it societal relationships.

A series of European diseases had greatly effected the Coast Salish people over the years but when small pox arrived in the 1860s it had a particularly devastating effect. The population balance shifted significantly and for the first time Europeans began to out number Indigenous.

Victoria continued to expand rapidly as salmon canning and seal hunting became industrialized. The significance and value of Camassia was lost, it was dubbed a noxious weed that required extermination. It being noted at the time, "If [bracken] fern prevail on the land, it should be ploughed up in the heat of the summer, in order, by exposure of the roots to the rays of the sun, to destroy them. These with all bulbous weeds, such as crocuses, kamass [camas], &c., should be collected and burned. Fern-land, not required for immediate use, may with advantage be left for hogs to burrow in, as they form valuable pioneers."

The 1870s, brought confederation and the introduction of the Indian act, eventually resulting in the establishment of residential schools and the further suppression of indigenous social, political and religious events. By 1911 most of the Islands Indigenous population were either relegated to reserves or forced to integrate. The once expansive Camassia meadows, reduced to areas that couldn't be easily converted into something else.

Urbanization: late 1800s to late 1900s

The innate Englishness of the landscape was not lost on the colonists or their Victorian sensibilities. However it still had an otherness to it, the structure of Garry oaks were not seen as equal to that of the mighty English oak (with their highly valued, lumber-heavy trunks). The disjointed and twisting attitude of the Garrys grew on settlers though and eventually, Victoria, became known as, the city of oaks.

As early as 1898, residents complained when street trees were removed for development. By then the trees had been accepted as being a unique feature of the area; an element of the romantic scenery particular to the city. By the 1920's they were noted as, "pioneering landmarks" that should be conserved.

Extensive soil disturbance led European plant material (much of it willingly seeded by colonists) to become invasive. by 1876, Scotch broom, dandelions and English daisy's were all considered naturalized. Easily outcompeting native species including those found in the remaining bits of the meadow systems.

Modern-day

Much of the 20th century saw continued development of the Island with the addition of several highways (including the Trans Canada, plus BC Ferries) connecting residents to the mainland and the rest of Canada.

By the 1990s, conservation of the 1-4% of the ecosystem that was left had become a priority. The role of meadow systems like the Garry oak, were recognized for their importance in holistic environmental planning. Their function as carbon sinks and water filtration systems, as well as habitat for many diverse and rare species accepted as essential. The remaining areas found on the South island included a patchwork of meadows in and around residential neighbourhoods, parklands and Gulf islands. Stewardship programs between governmental agencies, local residents and community groups became focused on restoration and ongoing care.

By the later part of the 20th century, preservation of the Garry oak system began to get some serious attention. With many projects like the large scale removal of invasive plants, in particular, Scotch broom, taking place. Grassroots environmental groups were formed including the Garry Oak Meadow Preservation Society (gomps), a charity that helps preserve the remnants of the meadow landscape.

The Garry Oak Ecosystem Recovery Team (goert), a large non-profit organization with links to government, academia, First Nations, and the public is of particular note. They're currently working to build a system for stakeholders to share information, techniques, skills and resources for continued stewardship and restoration.

Many Coast Salish communities including the Lək̓ʷəŋən (Songhees) began to reclaim camas as part of the ongoing restoration of their cultural identity. Re-adopting traditional foods as a way to improve indigenous health and re-establish food sovereignty. Working to restore, encourage and protect areas where the Garry oak ecosystem endure, through traditional practices. Since the 90s, camas harvests have once again become an important cornerstone for cultural and educational purposes.

In the past decade, the University of Victoria introduced camas to its campus grounds as part of the Kwetlal Restoration project. And, Camosun college's IECC (Centre for Indigenous Education and Community Connections) partners with the Lək̓ʷəŋən (Songhees) Nation to host pit cooking demonstrations. It is all part of the greater effort towards reconciliation and de-colonization. Understanding the longterm effects of historical events on our culture through enthnobotany and horticultural practice.

Visiting

There are lots of great ways to visit and celebrate the Garry oak system. Some of the best public spots can be found within close proximity to Victoria, BC. Including Mill Hill and Beacon Hill parks that both feature examples of Garry oak habitat plus walking trails, shoreline views and more. Friends of Uplands Park Society hosts an annual Camas Day Celebration in Uplands park every May, in gratitude of community stewardship, volunteerism and of course the sheer beauty of the surroundings.

The Cowichan Garry Oak Preserve located just outside of Duncan, is one of the largest restored areas (23 acres) of the deep soil ecosystem. Here, the NCC (Nature Conservancy Canada) and its academic partners research ways not only to preserve existing pieces of the ecosystem but explore the possibilities of converting lands that have been lost to agricultural use throughout the Cowichan valley. If you're on the mainland, UBC Botanical Garden features a Garry oak planting among its extensive collections.

Garden Use

There are many native plant nurseries where species found in the Garry oak system are available for purchase both in British Columbia and the Pacific Northwest.

In particular, Camassia are also widely available outside of Canada. They can be used in a similar way to other spring flowering bulbs such as tulips and daffodils. Camassia's distinctive colouring, structure and form make them valuable as elements of mixed succession schemes in addition to block and mass plantings. Their unusual timing makes them uniquely suited to fill the space between the wilt of tulip blooms and the emergence of early annuals.They also naturalize easily and are considered deer-resistant. Just checkout #camassia for inspiration from the likes of @margaridasamaia and @jelle_grintjes .

For more information:

GOERT (Garry Oak Ecosystem Recovery Team)

GOMPS (Garry Oak Meadow Preservation Society)

Plus Dr. Nancy J Turner's books, of which there are many

Thanks for supporting our writing and indulging the results of our curiosity. Hopefully, you’ve learned a bit about this unique ecosystem that exists in our home province and perhaps even been inspired to get involved in this or other systems in your local area. It’s a fantastic way to reconnect with plants as a part of the greater natural world. And, to reclaim our part in them as humans, because they need us as much as we need them.

Sara-Jane at Virens Studio

Virens is a studio located in Vancouver, Canada that specializes in ecological planting and landscape design + urban greening consultation + garden writing. Get in touch today so that we can help you green up your city. And, don’t forget to follow us on Instagram @virensstudio.