Is There a Better Solution (Beyond Pesticides) for Invasive Insects?

I live in a city that’s (for the most part) been pesticide-free for at least 20 years. Here, they have been used sparingly, only against highly invasive species like Japanese knotweed and Giant hogweed. Recently I learned that my city is now starting a spray program in an effort to eradicate the Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica). A species that has found its way out of a containment zone that has been in existence in the nearby City of Vancouver since 2017.

I know that the municipality has few options in this matter, it is in fact up to a larger government agency whether or not they spray. What actually concerns me more, is that they haven’t put much effort, beyond a small press release through their website, into educating the public. The overall feeling of which is, we have to do this, it’s perfectly safe, so no biggie. This lack of transparency means that the public at large, not only have little idea that the program is happening, but also that privately owned land will likely not be a part of it. How can chemical intervention work if it’s only applied to some of the land? There are other issues too, like the moving of soil and plant material out of this newly expanded containment zone, that aren’t being shared with the larger group. It makes me wonder if we are actually trying to solve the invasive pest issue? or simply complying with regulations?

All of this leads my mind to some larger questions. Are these types of chemical-based programs effective? Should we be using ANY chemicals in our green spaces? What are the unforeseen ways that ‘safe’ pesticides can effect ecosystems in the longterm? Could these infestations be a part of the larger natural systems in play? and ultimately, is there something better that we could be doing instead?

It’s a lot to think about, and it’s also a heavy subject. So today, we’ll do our best to go through each of these concerns, relying on the available science, in an effort to begin a larger conversation about change.

Problematic Pests

Because they lack their natural counterparts, invasive species create an imbalance within localized ecosystems. They decrease crop yields, harm forestry, disrupt natural eco-services, and can vector human disease, in varying degrees.

A 2016 study found that invasive insects “cost a minimum of US$70.0 billion per year globally, while associated health costs exceed US$6.9 billion per year”.

Case Study

Spongy (aka Gypsy) Moth (Lymantria dispar)

In the late 1860's, disease decimated traditional silk moth populations. A gentleman named, Étienne Léopold Trouvelot, ordered a new and improved species as a possible replacement. The package that arrived from France contained Spongy (Gypsy) moth eggs. As he raised his new insects, some happened to escape into his backyard in Medford, Massachusetts, and began to reproduce in the wild. What he didn't know, was that Spongy moth caterpillars feed on 300+ tree and shrub species.

In the 150 years since, the moth has spread (mostly via firewood) to more than two dozen states and provinces in North America. They are responsible for the defoliation of a million or more acres of forest every year.

Today, there are extensive monitoring and control programs in place, in an attempt to limit their spread, but there is little hope for eradication.

Spongy (aka Gypsy) moth

Do Pesticides Work?

Whether alien species are released on purpose or not, this is an issue that’s been around since the beginning of time. As humans travel, insects tend to tag along. In an effort to mitigate the damage we’ve thrown all kinds of controls at the problem: cultural, host resistance, physical, mechanical, biological and of course chemical.

According to the EPA, "a pesticide is any substance or mixture of substances intended for preventing, destroying, repelling or mitigating any pest. Though often misunderstood to refer only to insecticides, the term pesticide also applies to herbicides, fungicides, and various other substances used to control pests."

Why use Pesticides?

Chemical controls offer advantages such as:

convenience - they are readily available, take effect quickly and disseminate easily into the environment, covering a large area with few resources

costs - they require less resources to use, as compared to other methods

Disadvantages include:

health - chemicals are difficult to fully control and use without effecting non-target organisms

resurgence - natural control methods (predators) are removed causing long term imbalances in the ecosystem

resistance - pests natural ability to reproduce and evolve quickly makes chemicals less effective over time

persistent organic pollutants - ‘forever’ chemicals (POPs and PFAS’) used in the formulations of pesticides can poison non-target organisms over the long-term

costs - the imbalances caused by chemical usage create an ever increasing need for newer and larger amounts of chemicals to continue to get the same results, creating dependance on their use. (it is estimated that crop losses to pests would increase only 10% if no pesticides were used. Between 1945 and 1989, pesticide use in the U.S. increased tenfold and yet crop losses doubled from 7-14%)

"Global pesticide use has soared by 80% since 1990, with the world market set to hit $130bn this year, according to a new Pesticide Atlas."

Is it Possible to Eradicate Invasive Species?

When researchers gathered data from 173 eradication programs worldwide (involving 94 species), they found that 50.9% had been successful. They then pinpointed the elements that were more likely to succeed. These included:

controlled (manmade) environments - greenhouses especially.

local infestations - where a single agency was involved.

cooperation between agencies when programs crossed borders.

the type of pest involved - pathogens, bacteria and viruses were more successful, plants and invertebrates were intermediate and fungi were the least likely to be eradicated.

early starts - programs begun before critical thresholds were reached (within four years of initial infestation).

Case Study

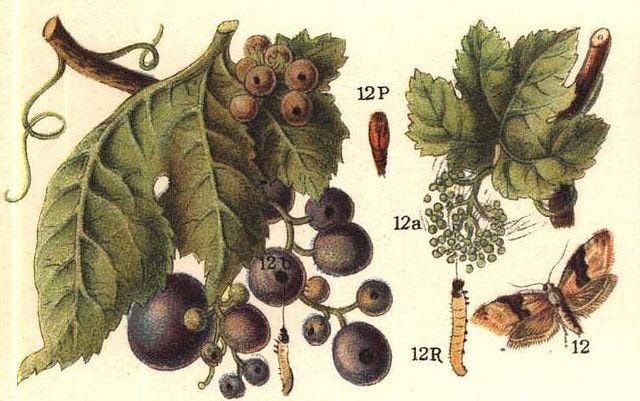

European Grapevine Moth (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae)

In 2009, Grapevine moth was detected in Napa County, USA. The response was immediate, a cooperative was formed between local, state and federal agencies, and experts. The resulting recommendations saw pheromone baited traps deployed across California. These were then used to pinpoint infestations and establish quarantine areas.

By 2010, an eradication program was put into action in cooperation with grape growers, the wine industry, researchers, and local, state and federal officials. Their actions included ongoing monitoring plus containment procedures to limit the movement of plant material and equipment in effected areas. Mating disruption and insecticide treatments were used where needed in commercial vineyards. With added, residential vine inspections and fruit stripping/treatments used where required. Additional outreach efforts plus a supportive research program were also created. The program continued until 2016, when the moth was successfully declared eradicated (after several years of moth-free monitoring).

European grapevine moth

Are ANY Chemicals Safe in the Landscape?

When I read my cities press release, there was a lot of reassuring language that stated how free from danger the spray program is. But, I would be remiss if I didn’t note that I’ve heard this before. Products that claim to be harmless, have a history of of being found incorrect. There are often hidden, unforeseen and uncounted effects from pesticides, found years after exposure, even with those tagged, ‘safe’.

Wildlife is often a good indicator of the greater ecological health, what are they telling us about pesticides that we don't already know?

Birds

Our avian friends are a good example. It’s estimated that 672 million birds are exposed to pesticides every year on US farmland. Of those, some 67 million (or 10%) are killed. This is a staggering number, however, it only includes birds that are killed directly through ingestion, in agricultural areas. These numbers are not able to give us any information on the chemical toxicity, amount and length of exposure, nor the effects of multiple exposures. It also fails to quantify ‘sub-lethal’ effects that can include:

eggshell thinning

deformed embryos

slower nestling growth rates

decreased parental attentiveness

reduced territorial defence

lack of appetite and weight loss

lethargic behaviour (expressed in terms of less time spent foraging, flying, and singing)

suppressed immune system response

greater vulnerability to predation

interference with body temperature regulation

disruption of normal hormonal functioning

inability to orient in the proper direction for migration

As we use a greater number of chemicals in ever changing forms and formulations, we continue to mark a wide variety of unintentional effects from pesticide use. These include things like, fertilizers that effect electromagnetic field of flowers and disrupt pollination. The death or mutation of soil micro organisms that provide protection and nutrient uptake in plants. Plus issues like, biomagnification, when the cumulative effects of a given chemical increases as it moves through the food chain.

Case Studies

RoundUp (Glysophate)

A widely available weed-killer, the use of Roundup has increased 100-fold in recent decades. Because it targets an enzyme that exists only in plants, it was once thought to be perfectly safe for non-target organisms. It is a broad spectrum, systemic herbicide, often used in landscaping and for large-scale crop production as part of preventative spray programs in conjunction with GMOs such as Roundup Ready corn.

“Glyphosate is the most used herbicide in human history: 18.9 Billion pounds (8.6 Billion Kilograms) sprayed worldwide since 1974.”

However, we now know that it is more persistent in the environment than first thought, with a long list of unanticipated effects. For instance, once the pesticide has absorbed into soils it can take more than 1000 days (2.7 years) for it to successfully degrade (depending on the soil type and conditions). With particles having been found as deep as 4.8m (16’). In fact, glysophate can now be found in water sediment, non-target plant material (including food crops) and even in falling rain and air. It can also measured not only in farm animal and pet urine, but also in humans (60-90% of Americans, 40-50% Europeans).

Some other lesser known effects include:

a shift in bacteria strains - killing off those that are susceptible and encouraging those that are resistant, which could lead to an increase in some harmful pathogens.

the widespread removal of milkweed species through regular spray programs may have reduced Monarch butterfly populations.

the reduction of a plants ability to fight off pathogens and take up nutrients - effecting mycorrhizae and interrupting the nitrogen cycle.

plants that can transmit glysophate to bees and other pollinators through pollen, which then is spread to larger communities via hives or nests.

gut health in animals and humans - affecting the functioning and health of the gastrointestinal tract, protection against pathogens and altering the endocrine and nervous systems.

Neonicotinoids (aka Neonics)

Neonics are a class of neuro-active insecticides chemically similar to nicotine. This groups include some of the most widely used insecticides in the world (including Imidacloprid, the top selling insecticide between 1999-2018). Broad-spectrum systemics, these chemicals are advertised as, "relatively low risk for non-target organisms and the environment". They are often applied as part of preventative programs including crop seed coatings, timber, home and pet (flea) treatments, as well as turf (Japanese beetle grub) and garden use.

Research now shows that neonics affect a wide range of non-target organisms (especially invertebrates), both directly and indirectly. Much like glysophate, they are systemic chemicals that need only come in contact with a single part of an organism to infiltrate it’s entire system. In addition they are water soluble, so if soil has been treated, or a seed coated, every time water makes contact with it, the chemical quickly spreads far and wide.

Some lesser known effects include:

treated cornfields that produced no increase in corn yields but did depress yields and profits in nearby watermelon fields by 21%.

a lake in Shimane Prefecture that has seen its commercial fishery collapse by more than 90% since treatment (Zooplankton—the tiny creatures in the water that fish feed on—declined by 83%).

correlated declines in some bird populations with environmental imidacloprid residues (linked to eating coated seed, using contaminated water and contact with effected plant material).

some evidence has linked neonics to reduced numbers of monarch eggs that are hatched.

the disruption of neurochemicals in mammals, leading to impairment and neurological damage.

amphibian decline (frog metamorphosis timing, body size, locomotion and reduced reproduction rates).

organisms feeding on exposed plant material passing neonics on through the food chain (biomagnification).

Neonics have also been linked to the decline in several bee species. Causing:

difficulty navigating

learning, and foraging

suppressed immune response

lower sperm viability

shortened lifespans of queens

reduced numbers of new queens produced

Camassia meadows, traditionally maintained through fire disturbance (Vancouver Island, Canada).

Disturbance Ecology and Pests

Disturbance Ecology

The natural cycle of landscapes includes disturbance. Where various actions including geohazards (eruptions, floods, drought and wildfires), animal behaviours, and human intervention, take place at various frequencies and intensities. This clears biomass from dense ecosystems in order to allow regeneration.

The inherent adaptability of insects (their small size, short life cycles and exceptionally fast reproductive rates) make them resilient to changing environmental circumstances. Marking invertebrates as one of natures most effective tools to help rebalance ecosystems, removing large amounts of plant material quickly, redistributing resources.

Prescribed burn area, transition from pre-burn to two years post (2008).

Case Study

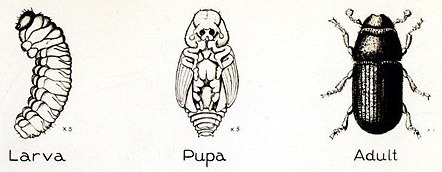

Mountain Pine Beetle (Dendroctonus ponderosae)

The Pine beetle is native to western North America, where regular short-term outbreaks occur (4-5 in the last 100 years). They are generally controlled by low temperatures and the natural defence mechanisms of healthy trees. However, the late 1990s saw climatic events (drought, temperature changes and long-distance dispersal winds) that pushed the beetle beyond its historic range, and into the interior forests of British Columbia, Canada. When this coupled with the existing, large dense, homogeneous forest stands (influenced by fire suppression and harvest regulations) what resulted was the largest outbreak ever witnessed.

This 'mega-infestation' took place between 1999-2015. At it’s peak in 2005, approximately 140 million m3 were under attack. Since then, there has been a rapid decline in infestation and further outbreak. The overall result has seen the destruction of approximately 58% (752 m3) of the mercantile pine volume in the province.

Today reduced supplies have effected timber prices and industry jobs, but also improved timber management practices. The outbreak has removed a great deal of the accumulated biomass, letting light into dense stands and allowing regeneration to take place. Slowly at first but speeding up over time (10-20 years post) with a greater diversity of species coming up in the understory. Many areas have required little to no restoration beyond their natural processes.

One study concluded, “a significant percent of residual secondary trees survived the beetle attack; stands in the current epidemic area appear to be recovering rapidly and in most cases can significantly contribute to mitigating the loss of mid-term timber supply; the occurrence of the MPB epidemic has resulted in more structurally and compositionally diverse forest stands” “likely to be more complex and heterogeneous in structure and, therefore, more ecologically resilient” when salvage operations are limited and deadwood is left intact.

Pine beetle

Lodgepole pine trees killed by mountain pine beetle near Bonaparte Lake, BC. Photo: K. Buxton, BC Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations.

Is There a Better Way Forward?

I recently heard someone speaking about the pesticide program in our area. In the course of the conversation, one woman asked the other, what would happen if we didn’t do anything? and let the beetles come? It’s an interesting thought.

I feel like the way forward is an open conversation centered around our collective priorities. What are the most important things for our world? Here are a few ideas that have been percolating in the back of my mind for awhile.

Celebrating Unconventional Beauty

For awhile now, we've been slowly learning to drop the traditional sense of beauty, rooted in order and neatness, in favour of more naturalistic green spaces. Parks and gardens that can give us some of the pattern and cultivated elements that we may crave, combined with the sensory experience that wild spaces bring.

Part of this shift, is learning to accept some forms of disturbance as natural and necessary events. That plant life and the larger landscapes have its own cycle of succession and we need to celebrate that in all of its parts (rather than continually attempting to freeze it at its flowery climax).

Another part of this, is helping to build strong resilient plant (and by extension, wildlife) communities by encouraging biodiversity, adding habitat areas and restoring affected areas. Both preventing invasive outbreaks and taking advantage of the natural cycles to help restore a functional ecological balance, when they do occur.

Planned Disturbance

In simplistic terms, this is about humans stepping in to replace the modes of disturbance that we have removed. This involves using a variety of techniques to reduce biomass. Which can include things like prescribed burns and reintroducing keystone species (grazers) into restored and rewilded ecosystems. Also, adjusting our conventional maintenance (mowing, haying and pruning) to mimic animal behaviour. Creating a mosaic of different ecosystems that build resilience and adaptability in the face of environmental change.

IPM 2.0

I feel like IMP (integrated pest management) has gotten a bad rap lately, due to its use of chemicals and focus on financial thresholds. However, I know that the principal is solid. Perhaps there's a way to introduce an, IPM 2.0? As our understanding of holistic ecology, insect lifecycles and their part in larger systems, continues to grow, can IPM grow alongside? Possibly including new methods of monitoring, wider ranging thresholds and a greater spectrum of treatments.

Functional Eradication

This is a strategy that focuses on suppressing populations of invasive species below levels that cause unacceptable negative impacts. Whether or not functional eradication will be an effective strategy can depend on several factors including, a species impact on ecosystems, their population dynamics and the distribution of habitat.

In other words, rather than spending all of our time, energy and money attempting to eradicate invasive species, we learn how to limit their impact and live with it, within reason.

Restoration of Effected Habitats

This involves areas that have spun out of ecological balance, whether from invasive species, natural disturbance or human intervention. It can include a whole spectrum of activities, from small-scale restoration projects to full-scale rewilding .

For some great examples,

Symbiotic Restoration - Restoring wetland habitat and supporting keystone species (beavers) across California.

Knepp Wilding - Large-scale rewilding, converting a traditional English estate into functional wilderness.

RiverLESS Forest - An innovative, mini forest springing up on the banks of the Beirut river.

Regardless of my personal thought process, the spraying will go on in my neighbourhood. But, I’m hopeful that we will all (as individuals, municipal employees and government agencies) find a better way to combat invasive species in the near future.

Sara-Jane at Virens Studio

Virens is a studio based in Vancouver, Canada. We specialize in Ecological Planting Design, Urban Greening Consultation and Garden Writing. Please get in touch today!