As do many of you, I’m sure, we have a Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus) problem. Yes, they may offer up delicious dark berries at the right time of the year, but their prickly canes will just as easily take your eye out and pull at your hair. They push in quickly and tend to take over, overstaying their welcome without any consideration for others (be it, humans, other plants or wildlife). And, worst of all they appear to be nearly indestructible, every bit of them that you chop off creates a whole new bramble (they boast 7,000-13,000 seeds/sq m, in addition to root and stem fragments).

A Scourge on the Land

Featured on a list of the world’s 40 most invasive (woody angiosperms), Himalayan blackberries prickly and prolific nature and tendency to colonize open/disturbed areas has effected millions of acres of woodland, farmland and riparian zones, forest margins and roadsides. Rapidly displacing indigenous plants and wildlife. Out competing through aggressive tactics, its dense (up to 3m) high thickets, block light while their large root systems soak up all of the available water. They decrease biodiversity and destabilize areas prone to erosion while being too dangerous for most animals to graze. A 2017 report suggests that Himalayan blackberry directly costs the economy some $20 million in Washington state alone (https://invasivespecies.wa.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/EconomicImptsRpt.pdf)

Thorny canes of Himalayan blackberry. (image: Korina 2011-08-08 Rubus armeniacus 15.jpg, cc 4)

So when I spotted them on the margins of our property, I began to feverishly research ways to tackle them (stay tuned to find out what method we decided to try). All of this, is precisely how I fell down a blackberry-hued rabbit hole that led me to one man, Mr. Luther Burbank.

It just so happens, that the Himalayan blackberry was purposely cultivated and introduced by Burbank in 1885. Presented as his latest creation, the “Himalayan Giant”. You read it correctly, one man did this.

Plantsman, breeder and all-around eccentric character, Luther Burbank, turned a berry, native to the Caucus (that’s right, it’s not Himalayan at all), loose on foreign soils. Where it continues to wreak havoc a hundred and 40 years later.

This is the point where I began to veer off course in my research. Just who was this Burbank dude? and where did he get off unleashing this beast of a plant?

Luther Burbank at age 19, (image: by an unknown photographer, c. 1868-1869, from the Digitl Commonwealth - commonwealth 02871m056.jpg)

The Ballad of Luther Burbank

Luther Burbank, was born (March 7, 1849) on a farm in Lancaster, Massachusetts. A precocious child (one of 15 in his family), he excelled at mechanics and held a deep love of nature. After his father's death and a move to another farm in Lunenburg, the young man began growing and selling vegetables. And, in his spare time, to tinker with plant breeding. Burbank started by growing on and carefully selecting the best plants from a rare potato seed ball found in his mother's garden plot. Which, after years of effort became the Russet Burbank potato (yes, that Russet potato, still the most widely grown variety nearly a century and a half on).

The Russet Burbank potato, (aka Russet potato) developed by a teenage Luther Burbank from seeds collected in his Mother's garden (image: 1914, public domain)

After some minor success, Burbank then travelled west to the considerably warmer climate of California. Where he settled into a home and gardens in Santa Rosa and started his 17 acre Experimental Farm a few kms away in Sebastopol. Then he really leaned into the progressive idealism of the age, and kicked his plant breeding into gear. He truly believed that if given a chance, he could improve the food supply and security of the world.

At one point, he attracted the attention of Clarence McDowell Stark, owner/operator of Stark Bro’s, Nurseries and Orchard co. Who saw both, the potential of Burbank’s breeding program and it’s lack of financial stability. It was Stark that paid Burbank $9,000 in exchange for three of the fantastic new fruit varieties that he had witnessed at the farm. Affirming the value that could be placed on Burbank's "new creations".

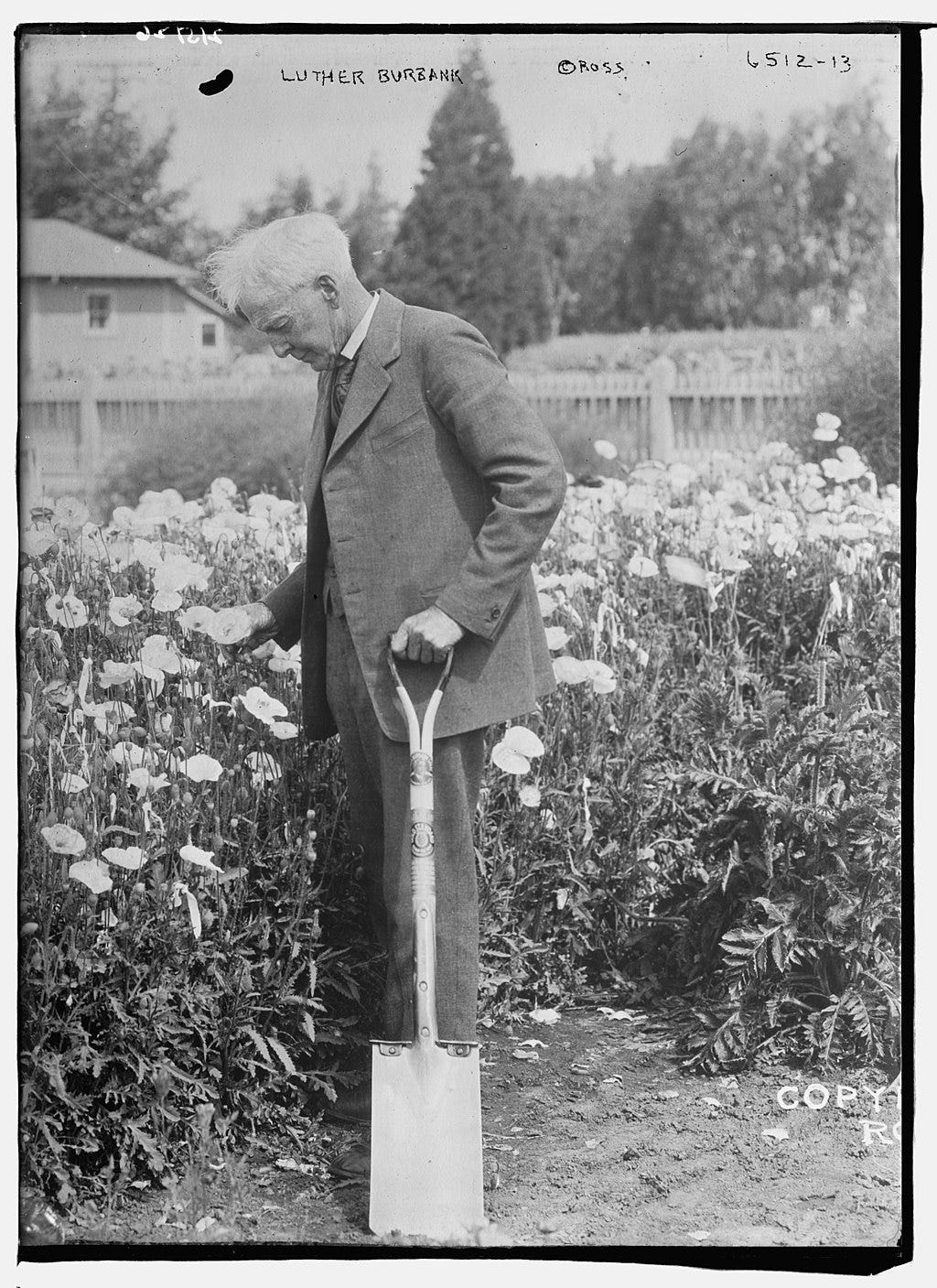

1900, Luther Burbank and his poppies. (image: Bain News Service, 1900, Luther Burbank LCCN2014719101.jpg, public domain)

Scientific Records are for Chumps

It turns out that Luther didn’t really see the need to write down what he did, or give a comprehensive report of his methods. After all, he had never progressed past a highschool education and didn’t consider himself an academic, but rather wished to be seen as an experimental scientist of sorts. Not to mention, he was a man of action in a hurry to change the world.

Instead of following a set scientific method, his practices were more generalized and some might say haphazard. Burbank would often make crosses between varieties of closely related species. Growing as many as 10,000 hybrids from a single pairing. He would then select between 1 and 50 of the best seedlings for a second-generation of hybrids. Only those that met the specific characteristics that he was looking for or showed the greatest variability were kept. From these few special plants, he would then further hybridize or backcross to produce another batch of seedlings. Selecting the best out these subsequent generations and working to fix traits that would breed true. All of this continued, until he produced the results he wanted in one single Mother plant. which could then be cloned indefinitely, producing thousands of identical plants year after year.

Although this often took years (and occasionally decades), he found ways to speed the process along. Burbank sometimes made hundreds of grafts on a single tree. Or tried dozens of experimental techniques at the same time, on the same plant. Maximizing the possible results while eliminating any research, exclusionary actions, controls or record keeping.

A 53 year-old Burbank in 1902. Who has time to make notes? (image: Shaw Photography, 1902, public domain)

Celebrity, Birth of a Plant Wizard

Soon, Burbank’s uncanny ability for selection and speed in producing new varieties began to spread. That’s right, Luther Burbank aka the “Plant Wizard” not only garnered a cool nickname, but his very own Fan club, the Luther Burbank Society. Whose members helped to disseminate his deeds and developments to whomever would listen.

As word of his accomplishments advanced, Burbank was made an honorary member of the American Breeders’ Association (yes, it was a real thing).

He also struck up friendships with the likes of, Thomas Edison and Henry Ford (now there’s a combo). Joining in on their famous road trip adventures along with, Harvey Firestone (of the tire co.) and naturalist, John Burroughs. With the men making a visit to the California farm to marvel at it’s wonders. It was through these connections that Burbank is said to have inspired Edison’s (and Stark’s) work to patent plant varieties on behalf of breeders.

Henry Ford, Thomas Edison, and Luther Burbank surrounded by crowd, Santa Rosa, California, 1915. (image: US National Parks Service, 1915, public domain)

Indeed at his zenith, Burbank could do no wrong and was widely praised and admired not only for his gardening skills but for his “modesty, generosity and kind spirit”. Beloved for his can-do work ethic, his interest in educational reforms and his unending work to feed the world. He quickly became an influential figure to be admired by the masses.

In 1904, his efforts attracted a series of grants from the prestigious Carnegie Institution. But these fizzled out after 1909, when they sent along an observer to see how Burbank's work was progressing. Unfortunately, his lack of scientific method became glaringly apparent and his experiments were deemed to offer exactly zero value to the greater community. Noted, were his tendencies to try many crosses on the same plant and even within the same flower, coupled with a lack of prevention (to stop any natural hybridization from occurring). This, in addition to his failure at record keeping, meant that any positive results could never be reliably duplicated. That being said, this small misstep did little to slow Burbank down.

Luther Burbank and Thomas Edison, California, 1915 (image: Thomas Edison and Luther Burbank (ec7403969b5f47d089185274f6c11a65).jpg, public domain)

Achievements

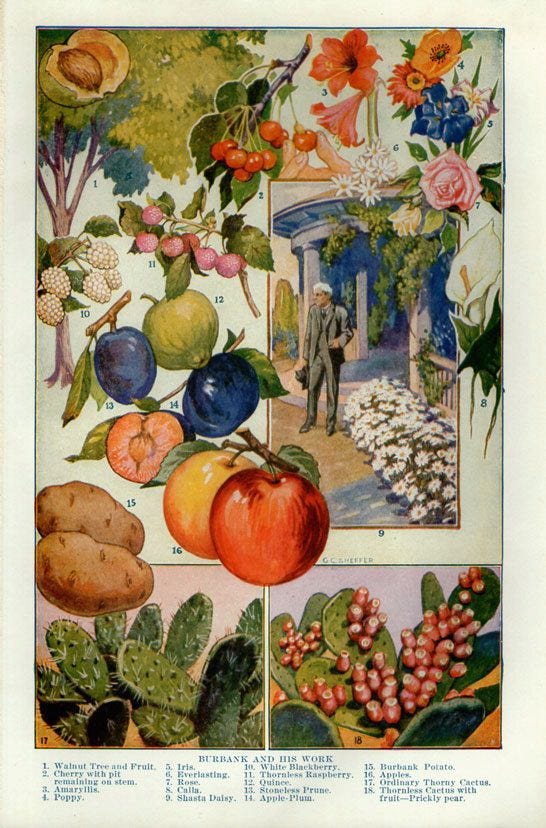

Luther Burbank's achievements were hard to deny. Prior to his intervention, chestnut trees took 25 years to bear fruit. He managed to develop varieties that could do it in three. He produced a white blackberry so clear that the seeds could be seen inside. Plus, a peach that not only peeled easily but whose pit dropped out readily. His dreams of vastly improving the world's food supply did have some merit after all.

In fact, over his 55 year career, Luther Burbank developed 800+ unique varieties and plants.

Including:

35 varieties of fruiting spineless cactus that could be used to feed livestock in desert regions

11 varieties of Plumcot (a tasty plum-apricot hybrid)

91 ornamentals from the Shasta Daisy to a fragrant Lemon Calla Lily,

a crimson version of the golden orange California state native and Giant Amaryllis

113 plums and prunes including, the “Miraculous” stoneless, “Wickson” and “Santa Rosa” (a large red skinned, golden fleshed, freestone favourite)

5 Nectarines, like “Flaming Gold”

8 peaches such as freestone and “July Eberta”

26 vegetables including the Russet Potato (bred to resist Late Blight, the cause of the Irish Potato Famine and now found on grocery shelves everywhere)

13 types of raspberry

16 varieties of blackberry, including “Snowbank” white blackberry and of course, the “Himalayan Giant” (that started this all)

10 Cherry

10 Strawberry

10 Apple

9 varieties of grass

4 Grapes

4 Pear

3 Walnuts including “Paradox” (a tree that grew 60’ tall in 15 years while others took 50+ to mature)

2 Figs

and an Almond (please note: you’d be forgiven if you finished with, …and a partridge in a pear tree)

It is important to note, that not all of Burbank’s experiments netted positive results. There were a few missteps, such as a cross between patunias and tobacco. Which ended up producing a tobacco plant that shot out patunia flowers and was ultimately too weak rooted to continue with. Or how about the Pomato, a kind of tomato on top, potato down below. Which wasn’t actually a cross between the two but instead, a potato that he bred to have tomato-like fruits. Something he made once but could never reproduce. And of course there is the “Himalayan Giant” blackberry, widely considered another Burbank success, until it wasn’t.

Some of Burbank's most famous "creations" (image: public domain)

Prolific Author

Not much of a public speaker, Burbank began publishing descriptive catalogs of some of his best varieties as well as several essays. Which kicked off a whole new phase of his career. Introducing, Luther Burbank, author. Just check out a sample of his titles:

The Training of the Human Plant (an "essay on childrearing”)

Some Interesting Failures: The Petunia with the Tobacco Habit, and Others

The Almond and Its Improvement: Can It Be Grown Inside of the Peach?

The Tomato and an Interesting Experiment: A Plant which Bore Potatoes Below and Tomatoes Above

Short-Cuts into the Centuries to Come: Better Plants Secured by Hurrying Evolution

How nature makes plants to our order

How Plants Are Trained to Work for Man

Luther Burbank, Plant Wizard (image: public domain)

Fall From Grace

Around 1916, cracks started to appear in the stature enjoyed by Luther Burbank. And even though he claimed to have unlocked the laws of plant improvement, many began to question his credentials (in addition to the Carnegie).

Since his earliest years in business, Burbank’s reputation and livelihood had relied on the sales of his many, “new creations”. Some of which he had developed, while others were later found to be a mix of plants: grown from foreign seeds (including the Himalayan Giant which Burbank had actually come from a packet of Armenian seeds sent to him via India), already existing varieties, improved varieties and even some standard varieties that had merely been renamed.

There were also challenges with the plants themselves. Some buyers took issue when comparing what they were able to grow, with what was promised. This included his catalog's failure to note what a dramatic effect climate and soil conditions (away from Santa Rosa) would have on plant performance. Also, that even if initial success was witnessed, many plants would quickly revert without specific maintenance practices. Losing the very characteristics that they had paid for. For instance, a rose bush that had been sold with huge pink blooms, might start producing small yellow blooms. Or a tree bought for large sweet apples could revert to sour disease prone fruit. Leaving customers upset and unhappy.

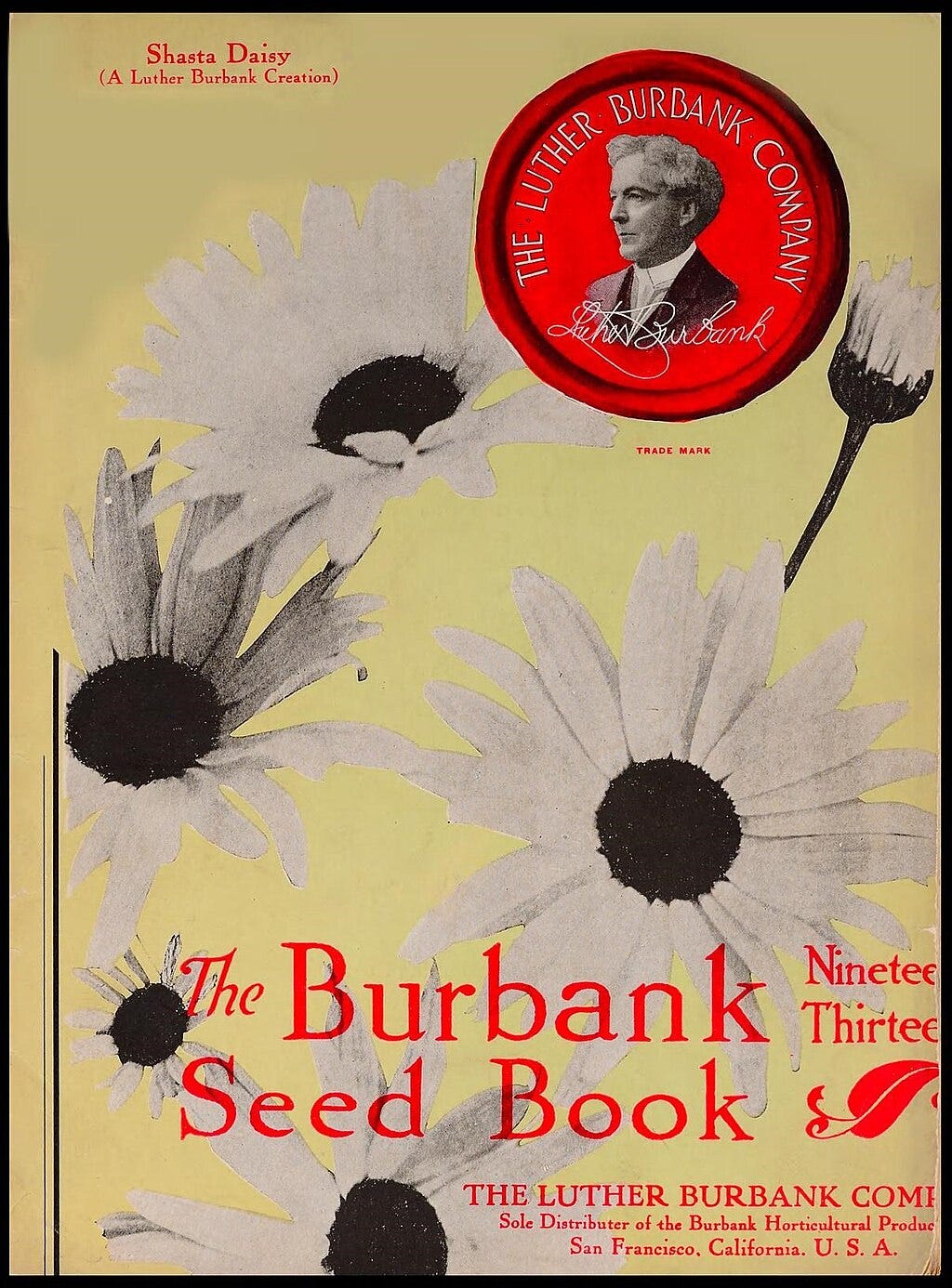

The Luther Burbank co., Seed catalog, 1913, featuring his Shasta daisy. (image: The Burbank seed book (16181185056).jpg, cc 2)

In 1912, the Luther Burbank Company was formed as a holding place for all of his propagating and marketing ventures. In which Burbank had chosen not to invest in personally, nor to hold any stock. Instead, taking periodic cash payouts in exchange for his involvement. Unfortunately, just four years after its inception, the company’s lack of accountability and quality control ended in bankruptcy. Leaving many angry investors facing a substantial financial loss and Burbank back in full control of his products, not having lost a cent.

Even his much lauded writings took a hit. Sited as failing to offer anything beyond common knowledge. Most of his volumes giving advise including, the provision of “good” soil, weed and pest control, plenty of sunshine, space and water. There were no real revelations, nor details of any true experimentation in regard to his theories on heredity.

Eugenics and Other Unusual Ideas

As you can imagine in an era of progressive ideas, that featured huge economic growth, prosperity and freedom, there were also some rather questionable progressive beliefs about. And, our man, Luther Burbank, fit right in.

Much like plants, he believed human beings should also be selectively bred, and became an active member of the American eugenics movement.

In 1906, he was elected to the American Breeders’ Association's Committee on Eugenics. Which at the time, was considered an honour. It was chaired by the chancellor of Stanford University and boasted members including the likes of Alexander Graham Bell (famous telephone inventor and lesser-known sheep breeder).

As a eugenicist, Burbank promoted genetic discrimination and the crossing of human species, as a way to breed out “unfit” qualities. But his staunch belief in the inheritance of acquired characteristics, put him at odds with the mainstream movement of the time. While many others had begun to explain heredity through genetic mutation and dominance, Burbank remained steadfast in his own covictions. He believed in Lamarckian theories, where environmental stressors were deemed to cause the emission of “hereditary particles” that altered reproductive cells. A well known example stating that, if a giraffe stretches it’s neck out to reach leaves, enough times over many generations, eventually giraffes are born with long necks.

In Burbank's eyes, the US as a vast source of diverse biological material, that could be blended through hybridization. And concluded that the country should “prohibit the… marriage of the physically, mentally and morally unfit”. Raising any resulting offspring in only the most favourable conditions. Placing: “love, honesty, self-respect, absence of fear, sunshine, good air, and nourishing food” above all else. He also added that children shouldn’t see the inside of a public school until they were at least ten years old. As he felt the American educational system of the time was intrinsically abusive.

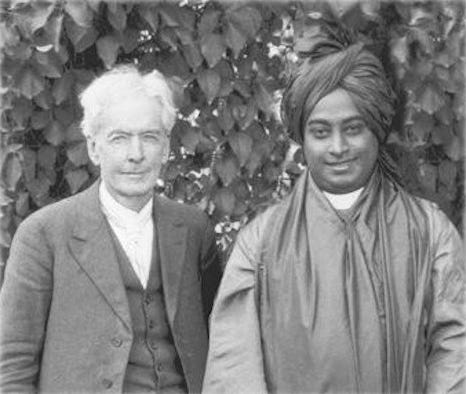

In 1924 Burbank wrote a letter endorsing the "Yogoda" training system. Which he had likely encountered during, Yogi Paramahansa Yogananda’s lectures in the United States (1920-1935). During which the Yogi introduced western audiences not only to Kirya Yoga and meditation. Emphasizing unity among the world’s great religions and espoused individuals building a direct connection to God. Ideas which were diametrically opposed to the social norms of the era.

These and other of Luther Burbank’s fringe beliefs stoked a great deal of public controversy when, a few months before his death (April 11, 1926), the 77 year-old detailed them in a San Francisco Bulletin article.

Luther Burbank and Paramahansa Yogananda, 1920 (image: public domain)

Burbank's Legacy

After his passing, but Inspired by his work (and spearheaded by Stark and Edison), the first Plant Patents were issued in 1930, under the Plant Patent Act. In fact Burbank’s old friend, Thomas Edison testified before Congress in support of the legislation stating that, "This will, I feel sure, give us many Burbanks.”

Additionally:

Burbank was posthumously issued 15 Plant Patents.

In 1909, California’s Arbor Day (later Arbor Week) was made March 7, Luther Burbank's birthday, in his honour.

In 1931, Frida Kahlo was inspired by Burbank’s grave, under a large tree on the farm, to paint a surrealist portrait. Where Luther Burbank is depicted as a half man, half-plant. His tree-trunk legs connected to roots, fed by his interred corpse. The ultimate statement of, "the fertilization of life by death”.

In 1940, the U.S. Postal Service issued a 3-cent, Luther Burbank stamp.

The Luther Burbank Home and Gardens, in downtown Santa Rosa, became a designated National Historic Landmark (as did the Experiment Fram in Sebastopol) and both remain open to the public.

The home that Luther Burbank was born in, as well as his California garden office, were moved by Henry Ford to Dearborn, Michigan, where they became part of Greenfield Village.

In 1950, the Santa Rosa, California Rose Parade was renamed as, Luther Burbank Rose Parade and Festival, to celebrate his contributions to horticulture.

In 1986, Burbank was inducted into the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

The Burbank stamp, 1940 (image: US Postal Service, 1940 FamAmer d 3.png, public domain)

In Conclusion

In the years following his death, Burbank’s widow, Elizabeth sold much of his estate to the Stark Bro’s. Including the exclusive rights to his experimental work at Sebastopol. This opened up hundreds of never marketed varieties (120 plums, 18 peaches, 28 apples, 500 hybrid roses, 30 cherries, 34 pears, 52 gladioli and more) for the Stark Bro’s to introduce under their brand. Some of which are still available today.

In modern times, Luther Burbank is less well known. As more and greater advances in plant breeding have been made over the years, his influence has faded. In fact, Burbank rarely even garners even a brief mention in modern academic textbooks. Being viewed by many as an eccentric, well-meaning but scientifically misguided plantsman or a charlatan. With most scholars, noting that Burbank at most had not actually created any new species, but merely recombined traits from the parent species or varieties.

Portrait of Luther Burbank, 1931 by Frida Kahlo

Rabbit Hole Over

And with that, I broke away the quagmire that is the story of Luther Burbank. Now, back to my quest to tame his, Himalayan blackberry.

For anyone interested, we decided to cut our brambles to the soil level. Covering the stubble with a thick (6mm) layer of UV-resistant agricultural grade plastic. We’re planning on leaving this in place for months (up to a year or more), in an effort to starve the root material from water, light and nutrients. With a plan to replant a pallet of more functional and less troublesome plant material. we’ll keep you posted.

As I stare out at the spot where our blackberry used to billow out of the soil, I can’t fight one thought curiously percolating in the back of my mind, what other (good and/or evil) wonders might this unconventional Plant Wizard inspire in the future? Who else is out there, fancying themselves an expert, tinkering with plant genes without fully realizing the consequences?

Sara-Jane at Virens Studio

Virens is a Studio on the westcoast of Canada, that specializes in Ecological Landscape and Planting Design, Consultation and Garden Writing. Drop by our website and IG profile to say hello today!

As a.ways, a great article!

No one really knows the consequences of their plant breeding but I don't think that should stop us! What impressed me most with Burbank is how he was willing to try early wide hybrids, like Blackberry and Apple(!) Or as you said, Petunia with Tobacco. Rather than view them as failures, we see these attempts as illustrations on how leaky the Linnean system is (for plant breeding).

With regards to the astonishing vigor of the Himalayan Blackberry, I will put forward to you that that is how all plants evolve. They compete and the most adaptable excel until another comes along.

One of the problems with this native-invasive argument is how static in time it is. Native to which time period? Invasive when? Surely the intermingling of species is how new ones are produced.

Let's not forget humans are the most invasive of all species.

Back to your Blackberry problem, I've heard that laying down a steel mesh with spacing slightly smaller than the diameter of a mature stem will cause the plant to continually girdle itself with new growth to exhaustion and death. Probably worth a try, and saves on buying other material.